Why Adrian?

Whatever your background, Adrian College can provide you with the skills and experience you need to realize your dreams.

Why Adrian?

Whatever your background, Adrian College can provide you with the skills and experience you need to realize your dreams.

Undergraduate Studies

We offer an undergraduate program of study that’s small enough to be personal

Graduate Studies

Pursuing your dream career starts with the next phase of your education. When you enroll in graduate school at Adrian College, you’re beginning more than advanced training in your field; you’re accelerating your professional journey.

Posted Thursday, October 20, 2022

Author: Mickey Alvarado

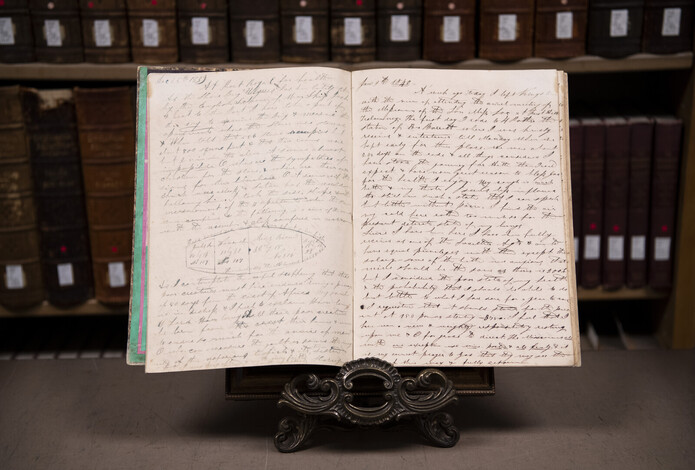

A diverse group of 14 scholars, including former Adrian College chaplain Christopher Momany, have crafted the first draft of a book about Christian abolitionist David Ingraham’s 1839-1841 journal that details his missionary work in Jamaica, and documents the living quarters of a captured slave ship, the Ulysses.

In 2015, the journal was discovered by former Adrian College technical services librarian Noelle Keller, and Momany was called in to see if he could identify its author. He and his associates concluded the manuscript, currently archived in Adrian College’s Shipman Library, is the work of Ingraham.

Momany and the scholars who studied the journal, the Dialogue on Race and Faith (DRF) team, will be traveling to Benin, West Africa, the homeland of those freed from the Ulysses, in November. Momany will represent the group and give a presentation about Ingraham’s journal during an International Symposium on Black Slavery from the 16th to 19th Century.

The DRF’s new book about the Ingraham journal is titled, “A Prophetic Past: Abolitionist Christians Modeling Racial Justice.”

The group expects the book to be published in late 2023 or early 2024.

“This is an international project, given life by a specific Adrian College tradition of love and justice,” Momany said. “We hope to see this effort as a springboard for more creative and affirming conversation about race in America.”

Momany said Ingraham was a protégé of Adrian College’s founder, Asa Mahan. The group of scholars believe the personal connection Ingraham had with Mahan led to the journal eventually being found on the campus of Adrian College, more than 150 years after it was written. Mahan was a pastor at the Second Congregational Church in Pittsford, N.Y., where Ingraham was a member.

Imagine the disgust and dismay Ingraham experienced as he examined and documented the quarters of the Portuguese brig, Ulysses, just after it had been captured by the British while sailing from what is now Benin, Africa to Cuba. The Ulysses was taken to Port Royal, Jamaica, where Ingraham was doing missionary work.

“When told that 556 slaves occupied but about 800-square feet and that their rooms were but 2’5” in the clear, it seemed almost impossible,” Ingraham wrote in his journal on Christmas Day in 1839 after touring the ship. “O where are the sympathies of Christians for the slave, and where are their exertions for their liberation? O it seems as if the church were asleep and Satan has the world following him… As I contemplate the awful suffering that these poor creatures must have endured during a passage of 50 days from the coast of Africa, my soul is in disbelief and I feel to exclaim, ‘How long, O Lord? How long shall these poor creatures be torn from their homes and made to endure so much for the avarice of men? O who can measure the guilt or sound the iniquity of this nefarious traffic and its twin sister slavery? O that I may pray often and with more faith for the oppressed.”

Four compartments were reserved for the slaves. As Ingraham notes in his journal, the rooms were only 2’5” high. At the bow of the ship was a room measuring 15’x12’ for 93 enslaved boys, while the section next door held 216 men in a 32’x’18’ space. Adjacent to the men were the women’s quarters, where 107 were confined in a 20’x20’ area. One-hundred and seventeen young girls were locked in the stern, in a room measuring 16’x’14.’

Ingraham describes the living quarters as being “nearly ankle-deep in filth.”

Twenty-three of the captives died during the journey crossing the Atlantic.

Ingraham’s journal has 100 pages of writing, beginning July 14, 1839. It includes passages detailing his newborn son dying soon after birth, his travels on horseback to preach the word of God, and tales of comforting strangers and friends on their deathbeds.

He also writes of not being able to shake an illness. On November 26, 1839 he wrote, “My health is at present quite poor. I have had a cold on my lungs for nearly three months also cough and often pain in the side… I hope I am not doing violence to my health and life in what I am now doing for it does seem absolutely necessary that things should be kept moving or much evil will result.”

Ingraham traveled back to America for a few months to improve his health, and on his return trip to Jamaica describes one of several disturbing incidents he witnessed at sea, “I am sorry and feel greatly pained to say that the poor sailors — sons [of] Africa, have been severely treated. Three of them have been severely beaten with large ropes for what I should call a very small offence — if offence at all. My heart yearned for them, and I felt to my very soul every stroke laid upon them or rough word spoken to them. They seem to suffer because they are black rather than for any other reason.”

The journal abruptly ends on March 14, 1841. On that day Ingraham writes, “I have felt of late that it would be our duty to return to America this spring as we are doing no good here or very little, and as there is no prospect of my recovery at present so as to teach or preach, and in fact my recovery seems almost impossible in my present situation of care and responsibility, and in my precarious state I feel it duty to place if possible my family among their kindred and friends so that in case I leave them they will not be alone or friendless.”

Ingraham died on August 1, 1841 of lung disease [tuberculosis] two years after documenting the slave ship.

Ingraham’s journal has been professionally preserved, and digitally scanned. It can be seen online at http://adrian.edu/library/theses/ingram_diary.pdf. Funding for research on the manuscript has been provided by Seattle Pacific University and the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

For more information about Adrian College and the Shipman Library, visit Adrian.edu.